Fighting West Africa’s Ebola Outbreak: What Lessons Can Human Rights Funders Learn from the Response?

John M Kabia at the Fund for Global Human Rights shares lessons for human rights funders following the experiences of local civil society and human rights organizations during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

John M Kabia at the Fund for Global Human Rights shares lessons for human rights funders following the experiences of local civil society and human rights organizations during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

It’s been over a year since the WHO officially declared the end of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the worst outbreak of the disease on record. While the immediate crisis is over, much remains to be done, and the response from governments, health providers, funders, civil society, local communities, and others leave us with vital lessons to be learned.

In March 2014, the first confirmed case of Ebola was announced in the Guinea’s remote forest region. The virus quickly spread to Liberia and Sierra Leone, infecting over 28,000 people and claiming the lives of more than 11,000. Decades of underinvestment in health systems and social services, corruption, lack of transparency, and a deep mistrust of government and official institutions created the perfect conditions for the spread of the virus. As such, the outbreak was both a health emergency as well as a crisis of human rights and accountability.

An effective response therefore needed to address the clinical, human rights, and social dimensions of the outbreak in communities. However, the initial response by governments in the region was heavily militarized, using excessive quarantines and lockdowns. This heavy-handedness deepened citizens’ mistrust and alienated local communities who were crucial to containing the virus.

Following a slow start, the Ebola crisis generated significant international support and media attention. Yet, for the most part, media coverage focused heavily on the work of international organizations with little mention of the critical role of local activists and communities. At the height of the outbreak in November 2014, I wrote a piece for the IHRFG blog in which I shared the concerns of many other local groups who felt left out of the inner circle of organizations receiving funding, and excluded from the policy conversation in-country, despite their active, frontline role in combating the disease.

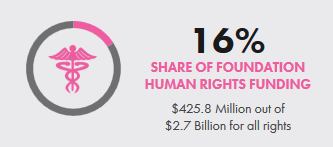

IHRFG and Foundation Center’s latest research on human rights grantmaking, based on 2014 data, appeared to support this claim. While health and wellbeing rights received more funding than any other human rights issue that year – both in Sub-Saharan Africa and globally – the data show that over 80 percent of funding for Western Africa went to groups based outside of the region. Nevertheless, the data also show a good number of local groups in the affected region received support towards health and wellbeing rights, more than in previous years. Nearly half of these grants mentioned Ebola specifically, with human rights funders supporting local activities ranging from awareness-raising to community dialogue and pyschosocial support for survivors.

IHRFG and Foundation Center’s latest research on human rights grantmaking, based on 2014 data, appeared to support this claim. While health and wellbeing rights received more funding than any other human rights issue that year – both in Sub-Saharan Africa and globally – the data show that over 80 percent of funding for Western Africa went to groups based outside of the region. Nevertheless, the data also show a good number of local groups in the affected region received support towards health and wellbeing rights, more than in previous years. Nearly half of these grants mentioned Ebola specifically, with human rights funders supporting local activities ranging from awareness-raising to community dialogue and pyschosocial support for survivors.

Grantee of the Fund for Global Human Rights, Defense for Children International-Sierra Leone educates community members about Ebola

Amid deep mistrust of state actors, local human rights and community groups were critical in the response due to their credibility, local knowledge, and extensive volunteer networks. With little support, these groups educated their communities on modes of prevention and hygiene practices to help break the chain of transmission, challenged the stigmatization of Ebola survivors – especially women and children –and supported their reintegration into communities. Local groups documented and challenged human rights violations perpetrated during the outbreak and monitored the allocation of resources, lifting up the importance of equity and transparency in the distribution of aid, care, and other resources.

What can funders learn from the experiences of local civil society and human rights organizations during the outbreak?

1. Adopt a gender lens

This health crisis exacerbated the vulnerabilities faced by women and children. In the initial response to this outbreak, the focus on their unique needs was severely lacking, even though women and children comprised the bulk of those affected. The response was also heavily male-dominated and highly militarized, inhibiting effective communication to women about their role in preventing transmission. One measure to prevent human contact implemented by the authorities was to close markets and impose quarantines – these measures hit women’s lives the hardest. Similarly, the breakdown of trust in the healthcare system posed serious threats to the health of pregnant women and children.

By taking a nuanced gender and human rights lens in their work, local groups were able to mobilize women to play an active role in the response and press local authorities to reflect the needs of women and children in their local Ebola response plans. In some of the first areas to be declared Ebola-free, we now know the contribution of women in eradicating the disease was critical.

2. Continue to support local groups already working on rights issues in affected communities, even if they might seem unrelated. There may be more to a health crisis than meets the eye.

Often, due to the scale of an emergency and the influx of outside groups, donors tend to overlook or overshadow local voices. As discussed above, local human rights and community groups played a key role in combating the Ebola outbreak in West Africa as well as in addressing the related social and human rights challenges. It is critical for human rights funders to support these frontline groups to enable them to adapt and scale up their interventions.

Governments and non-state actors alike often behave opportunistically in an emergency. They may use it as a pretext to pass highly controversial policies and legislation designed to roll back key freedoms. It is crucial that rights groups remain deeply engaged in communities.

In Sierra Leone, the government used the cover of Ebola and emergency regulations to crack down on critical media and civil society voices as well as make highly questionable constitutional decisions including the sacking of the country’s vice president. In Liberia, Global Witness described how an oil palm company, Golden Veloreum, operating in Southeastern Liberia increased its land acquisition by up to 100 percent at the height of the Ebola outbreak. When communities staged a peaceful demonstration in May 2015 to challenge this, the government sent security forces to arrest and detain over a dozen local activists. And in Guinea, the National Assembly passed a law banning spontaneous demonstrations and giving the security forces powers to use any necessary means to disperse protesters – effectively a license to kill in a country known for its impunity.

In West Africa, while governments and big international organizations focused on addressing the medical aspects of Ebola, less attention was given to addressing the related social and human rights challenges exacerbated by the outbreak. Thus, in both Liberia and Sierra Leone, there was a sharp rise in rates of sexual violence, while systems and structures designed to support victims nearly collapsed under the weight of the outbreak.

We as human rights funders often refer to “intersectionality” in our work. The indirect consequences of the Ebola crisis embody those intersections and make the case for funders to look beyond the immediate needs of the health crisis to the broader implications for civic space and human rights.

3. Flexible responsive funding is more important than ever in a health crisis.

The Ebola outbreak once again reaffirmed the value of flexible and responsive funding. Emergency and project grants are vital in responding to humanitarian emergencies, but equally important is the flexibility to allow groups to reprogram existing grants to respond in real time. In hindsight, it may be hard to believe, but during the Ebola outbreak and since, a number of groups in the region expressed frustration that they were not allowed to reprogram funding from some funders to respond to the crisis while some others were even asked to return grants already disbursed.

4. Coordinate, coordinate, coordinate!

Coordination amongst international and local actors was a major challenge in the response to the outbreak, but the truth is funders fell short, too. It was often unclear who was leading the response and how funds were raised and distributed. This lack of coordination and ensuing confusion led to unnecessary delays, uneven distribution of supplies, and tensions amongst responding organizations. While it is necessary to look at failures of coordination at that level, it is important to see how coordination can be improved among human rights funders. We might start by ensuring there is regular sharing of information on lessons and response strategies – for example, through IHRFG and Foundation Center’s Advancing Human Rights research – and where possible, engaging in collaborative initiatives.

5. Keep the horizon in sight.

Finally, even in the height of the response to a health crisis, it is critical that funders keep their eye on the long term, think beyond the immediate emergency phase, and develop strategies to address the long-term effects of the crisis. Funders can use this moment to take stock and respond to both the long-term impacts of the health crisis and the underlying causes of the outbreak. This includes addressing structural inequality between women and men, fighting corruption, and promoting effective health and social service delivery. The patience required to usher gradual social change may not be intuitive in the rapid response required for health emergencies. Yet as human rights funders, we have committed to supporting that long-term struggle. We can take advantage of our position to address the root causes and – perhaps – prevent the next crisis.

John Kabia is Program Officer for West Africa at the Fund for Global Human Rights. He holds a PhD in Conflict, Security and Development from the University of Bradford, UK and has authored a series of research publications on human rights, conflict, and peacebuilding in Africa.

The Fund for Global Human Rights supports the work of grassroots human rights activists and organizations across 20 countries in 6 regions. In West Africa, Fund grantees are involved in addressing a wide range of human rights issues, such as defending land rights of communities threatened by mining and agro-business concessions, promoting women’s and children’s rights, pressing for accountability for war crimes, combating corruption, and pushing for government policies that promote the economic, social and cultural rights of citizens.

During the Ebola outbreak, the Fund’s support to frontline human rights organizations in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone enabled them to educate communities on modes of prevention and hygiene practices to help break the chain of transmission; challenge the stigmatization of Ebola survivors, especially of women and children, and support their reintegration into communities; and document and challenge human rights violations perpetrated during the outbreak.