Modeling the Principles: Philanthropists have long been collecting artwork. It may be time they learn from artistic practice.

Our Human Rights Grantmaking Principles blog series is produced in collaboration with Ariadne and Gender Funders CoLab.

By Mariana Prandini Assis*

Federal University of Goiás

Last September, I had the chance to see the 15th edition of the contemporary art event documenta in Kassel, Germany. Initially, I was overwhelmed by its size. I kept folding and unfolding the map, my eyes zigzagging from one venue to another so that I could decide where to spend the 10 hours that I had for the visit. When I finally entered the first chosen room, filled with gorgeous carpets on its walls and comfortable colorful pillows to sit on its floor, two documentaries about Kurdish traditional forms of singing (Dengbêj) produced by the Rojava Film Commune were being screened. As I listened to captivatingly euphoric singers who have kept the breathtaking tradition almost entirely unchanged explain that “the decay of this art means the defeat of humanity,” my brain turned to yet another dimension of documenta fifteen: Its singular and transformative mode of planning, production, and financing.

Philanthropy and art are closely connected. Throughout history, artists have relied on philanthropists to develop their work, and philanthropists have long been well-known art collectors and supporters. Following this existing connection, I want to suggest that philanthropists could learn a great deal from the redistributive practice that made documenta fifteen possible. This practice can model a view of social-justice philanthropy that not only gives voice to those who have been silenced by structural systems of oppression but also redistributes social, political, and economic power.

Indeed, rather than being envisioned by a single or a group of curators from the established art world, documenta fifteen was led by ruangrupa, an Indonesian art collective that received the mandate to run the show. ruangrupa launched a transformative participatory process of planning and distributing resources that they called Lumbung, the Indonesian word for “rice barn.” In this conceptualization, it means much more than a place that stores communally produced rice for future collective use. In ruangrupa’s own words, Lumbung expands documenta’s “noble intention to heal European war wounds… in order to heal today’s injuries, especially ones rooted in colonialism, capitalism, and patriarchal structures.”

Lumbung aligns with the calls to decolonize philanthropy that have become louder in the past few years. Organizations and activists from the Global South, working on various issues, have made it clear that the circuit through which coloniality of power extends itself via funding philanthropy’s priorities and practices must end. This requires giving back power to the most disenfranchised to decide where funds should be applied, how, for what ends, and to whose benefits.

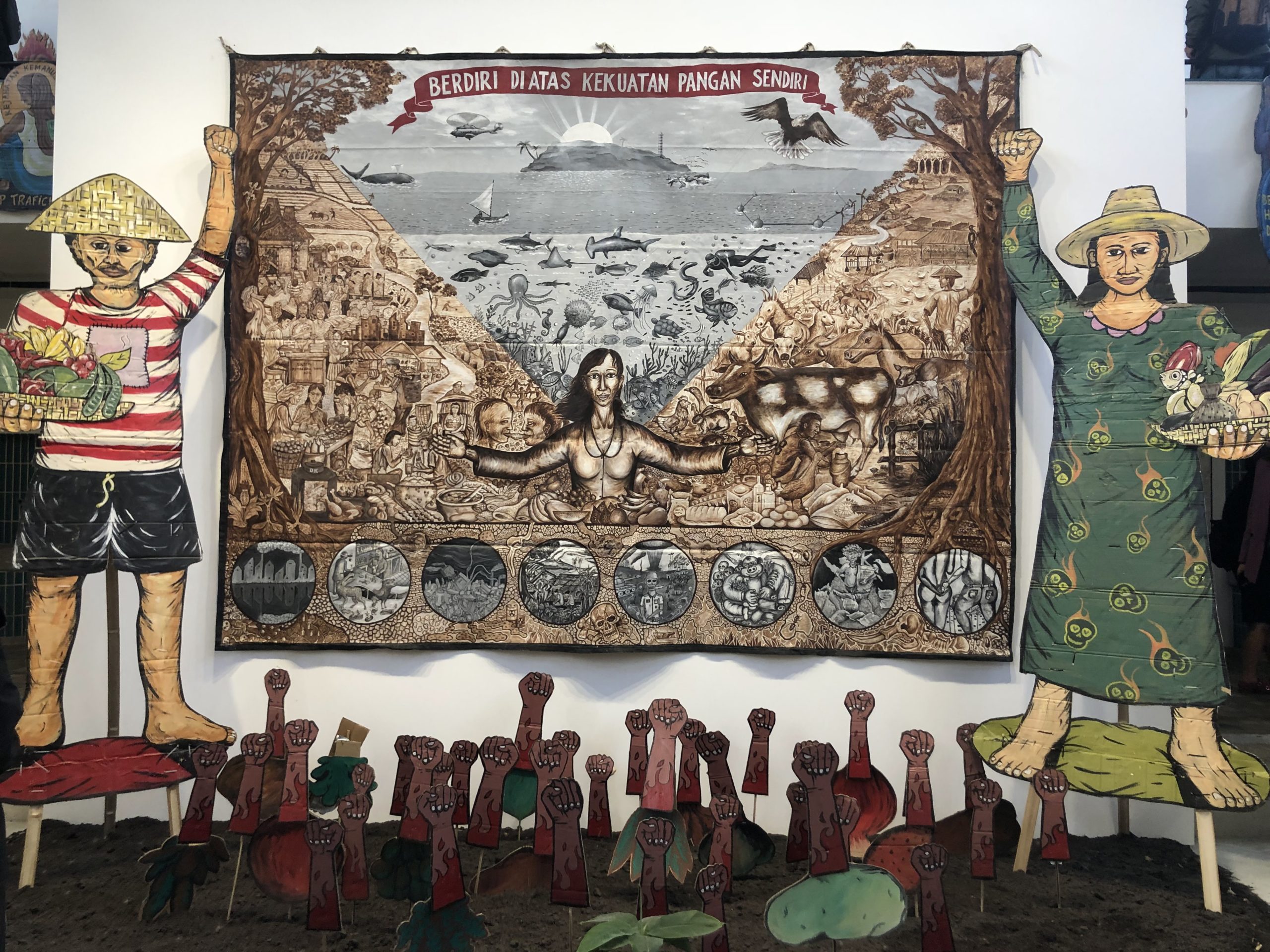

ruangrupa redisrupted power in the art world, leveraging documenta – a wildly popular and exorbitantly-financed art event – even further by introducing “a model of economy based on democratic principles of rapat (assembly), mufakat (agreement), gotong royong (commons), hak mengadakan protes bersama (right to stage collective protest) and hak menyingkirkan diri dari kekuasaan absolut (right to abolish absolute power).” That is to say, the collective allowed that the people involved in making the exhibition had the means to speak truth to power while also practicing different modes of relating to one another and to the public. Perhaps most importantly, ruangrupa distributed the common resource – documenta’s eye-watering budget – among a constellation of invited collectives and individuals, who in turn shared it with other collectives and individuals, resulting in over 1,500 participating artists. Contributors were mostly from the Global South with artistic practices that pay no respect to market or philanthropic forces.

If we take seriously the idea that philanthropists are people with resources to give who benefit immensely from the current system, the only way that their giving can be truly transformative is by funding practices that help dismantle that very system. This is what happened at documenta fifteen, whose entire budget was placed in the hands of a collective that instituted equal distribution of resources with no strings attached other than to commit to collective decision-making. The result was an assembly of open possibilities from different geographies that otherwise would not have been together; an assembly that practiced art for social transformation instead of producing objects for the artistic market.

Rather than controlling the process to successfully achieve a pre-established outcome, ruangrupa valued the process in itself and all the unexpected results it could bring about. This orientation stands in stark contrast to what philanthropists often do – in their attempt to avoid mishaps, many seek control over grantees’ narratives and practices. However, missteps are always a possible outcome of anything inventive, and disruptive. Every time we try to create something new, to produce innovations that make the world a better place, we may stumble. And these are the moments that we most need someone to hold our hands and believe that the process has value in and of itself. Long-term transformation requires time and often challenges our sense of stability, but above all it demands trust and flexibility. Lumbung provided this: a safe space that allowed for radical experimentation with transparency and accountability. And from this the philanthropy community has a lot to learn.

*Mariana Prandini Assis is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Federal University of Goiás, in Brazil, and a co-founder of the Margarida Alves Collective for People’s Legal Aid, a group of feminist antiracist lawyers who harness the law to advance movements for social and reproductive justice. She holds an LLB from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, and an MPhil and PhD in Politics from the New School for Social Research, in the US. For completing her graduate studies, she received fellowships from the Brazilian Ministry of Education, Fulbright, and the American Association for University Women. An interdisciplinary social scientist working at the intersection of law and politics, Mariana’s research areas include feminist political and legal theory, human rights, social movements, public policy, and informality in economies, institutions, and practices. Prior to joining the Federal University of Goiás, she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Schulich Law School at Dalhousie University, in Canada, and a special advisor to the President of the Interamerican Court of Human Rights.

*Mariana Prandini Assis is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the Federal University of Goiás, in Brazil, and a co-founder of the Margarida Alves Collective for People’s Legal Aid, a group of feminist antiracist lawyers who harness the law to advance movements for social and reproductive justice. She holds an LLB from the Federal University of Minas Gerais, and an MPhil and PhD in Politics from the New School for Social Research, in the US. For completing her graduate studies, she received fellowships from the Brazilian Ministry of Education, Fulbright, and the American Association for University Women. An interdisciplinary social scientist working at the intersection of law and politics, Mariana’s research areas include feminist political and legal theory, human rights, social movements, public policy, and informality in economies, institutions, and practices. Prior to joining the Federal University of Goiás, she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Schulich Law School at Dalhousie University, in Canada, and a special advisor to the President of the Interamerican Court of Human Rights.