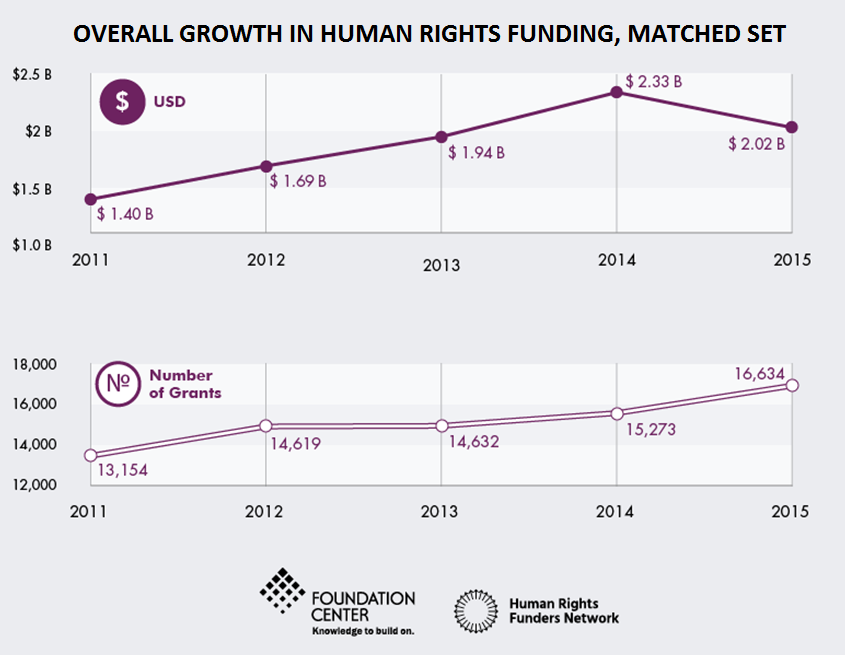

We analyzed any grant that met our definition of human rights funding, regardless of whether the funder self-identified as supporting human rights.The research includes funders making just a few human rights grants and those making thousands – and those grants range from multimillion-dollar core support grants to Human Rights Watch to a US$24 grant to support a feminist dialogue in Chile.What could be driving the increase in funding? We see a few explanations.

We analyzed any grant that met our definition of human rights funding, regardless of whether the funder self-identified as supporting human rights.The research includes funders making just a few human rights grants and those making thousands – and those grants range from multimillion-dollar core support grants to Human Rights Watch to a US$24 grant to support a feminist dialogue in Chile.What could be driving the increase in funding? We see a few explanations.

While we can’t speak to the unique priorities of hundreds of funders, it seems that some have actively devoted more funding to human rights, responding to new opportunities and needs on the ground.

The growth also reflects nuances in the data: funders submitting more – or more detailed – grants data each year, as well as more funders framing their work as human rights.

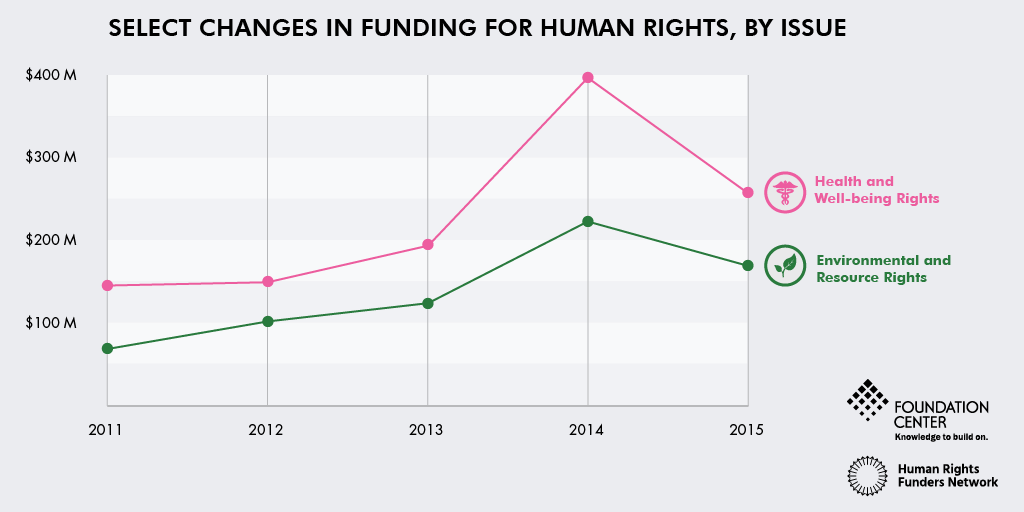

Several issue areas showed notable growth from 2011-15 among this matched subset:

Funding for Environmental and Resource Rights more than doubled, from US$69 million to over US$169 million.

- This is exciting but not necessarily surprising. The intersection of human rights and the environment increasingly pops up in conversations among funders, from local efforts at climate justice to security and protection for environmental activists. The data reflects increased funder engagement: 167 funders made an environmental and resource rights grant in 2015, an increase of 28% over 2011.

Funding for health and well-being rights grew from US$145 million to US$257 million.

- Like the environment, health can sit at the nexus of human rights and other fields like international or community development. US funders who don’t call their work ‘human rights’ are increasingly framing healthcare grants in terms of access and equity – essentially incorporating rights language. This shift in language and framing explains much of the growth. Indeed, in 2011, funding from those who don’t self-identify as ‘human rights funders’ accounted for 37% of funding for health rights. By 2015, this cohort’s funding grew to represent 51%.

The field of human rights philanthropy has grown, too, with new funders bringing both financial resources and their voices to specific issues. The Freedom Fund, for example, was established in 2013 to support frontline efforts to eradicate modern-day slavery. Funding for Freedom from Slavery and Trafficking has since nearly doubled.

FRIDA | The Young Feminist Fund, which supports organizing among emerging feminist groups, collectives, and movements, announced its first grants in 2012. Funding for grassroots organizing has more than tripled. These funders’ grants are notable, but they don’t account for this growth alone.

Did the creation of these new funds influence their peers – the power of funder advocacy – or instead reflect and harness movements already rising within the field?

Despite overall growth among this matched set, we’ve also seen notable dips:

Funding for disability rights dropped by 23% – the only one of the key population groups we track to see a decrease.

- However, the relatively small amount of funding for disability rights makes this area particularly susceptible to dramatic year-to-year shifts. The disability community has often had to make the case that they are a member of the human rights family. Ford Foundation’s recent evolution in this area, which they’ve shared openly with the social justice community, and a report from the Channel Foundation, Disability Rights Fund, and Wellspring Advisors illustrate this challenge. What work might funders still have ahead of them to fully recognize and integrate a disability lens in their work?

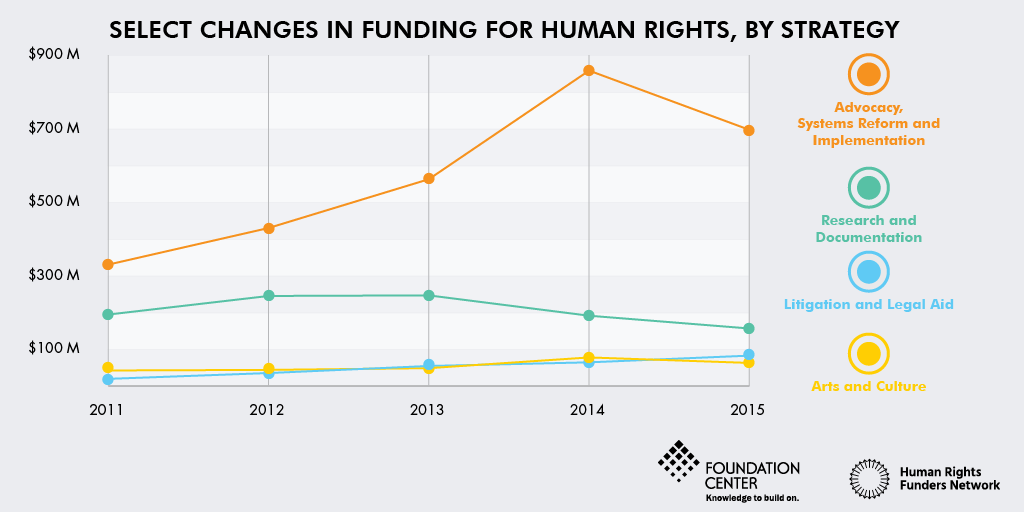

Support for research and documentation dropped by 19%.

- Of the eleven strategies we track, this may be closest to a traditional understanding of human rights work: fact-finding and documenting human rights abuses. It’s interesting to see that less traditional areas, such as arts and culture, and strategies aimed at achieving and sustaining systemic change, such as advocacy or strategic litigation, saw substantial growth while major funders’ investments in research and documentation decreased.

But perhaps the most striking dip isn’t a trend at all.

Overall human rights funding grew each year of the research, but it decreased in 2015 (to US$2 billion from US$2.3 billion in 2014).

We’ve found a few reasons why. Some are obvious – for example, the Atlantic Philanthropies, a major human rights funder, had mostly spent down by 2015.

Others can be easily explained – with growing concerns around civic space and digital security, some funders choose to share fewer details on grants, including major donors working in sensitive contexts.

Other shifts raise more questions than answers. Among those who identify as ‘human rights funders’ and those who don’t, does a decrease indicate a shift in their priorities?

Or is it just a blip on the radar? Short of digging through their strategic plans or eavesdropping on board meetings, we may not know until we see the next years’ data.

That’s the beauty of this trends analysis. Year-to-year fluctuations can be influenced by a number of factors: the actions of a few large foundations, a few major grants in a single year, and, yes, even a few key funders not having the capacity to share data in a given year.

Drawing from five years of data allows us to look beyond these caveats and identify consistent trends in the field. We can see where human rights philanthropy as a whole is headed – and where it still has work to do.

But do these trends reflect the reality of human rights movements? Will they continue? How well does this ‘matched subset’ reflect a broad and diverse field, anyway? A number of questions remain – we know.

We look forward to diving into them as we launch the trends analysis.

Starting in mid-January, we’ll explore some of these points in a blog series by your peers, and you’ll be able to examine trends in your specific area of interest on our research hub. We hope you’ll stay tuned.

Anna Koob is a Knowledge Services Manager at the Foundation Center and Sarah Tansey is the Program Manager for Research & Policy at Human Rights Funders Network.